The infection and immune life-cycle for Influenza A and similar enveloped viruses such as SARS-CoV-2 are varied and may depend on many factors. Several quotes from various reference materials included below provide a summary of the infection and immune life-cycle.

“Three requirements must be satisfied to ensure successful infection in an individual host:

- Sufficient virus must be available to initiate infection

- Cells at the site of infection must be accessible, susceptible, and permissive for the virus

- Local host anti-viral defense systems must be absent or initially ineffective.

“To infect its host, a virus must first enter cells at a body surface. Common sites of entry include the mucosal linings of the respiratory, alimentary, and urogenital tracts, the outer surface of the eye (conjunctival membranes or cornea), and the skin”

“Following replication at the site of entry, virus particles can remain localized, or can spread to other tissues”

“Viruses that escape from local defenses to produce a disseminated infection often do so by entering the bloodstream (hematogenous spread). Virus particles may enter the blood directly through capillaries, by replicating in endothelial cells, or through inoculation by a vector bite. Once in the blood, viruses may access almost every tissue in the host. Hematogenous spread begins when newly replicated particles produced at the entry site are released into the extracellular fluids, which can be taken up by the local lymphatic vascular system (Fig. 7). Lymphatic capillaries are considerably more permeable than circulatory system capillaries, facilitating virus entry. As the lymphatic vessels ultimately join with the venous system, virus particles in lymph have free access to the bloodstream. In the lymphatic system, virions pass through lymph nodes, where they encounter migratory cells of the immune system.”

Please read the following for more details regarding viral entry.

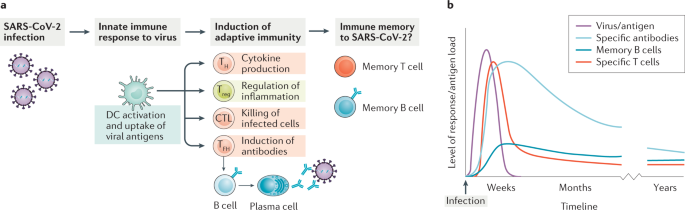

The immune system response to the viral entry is detailed in the following materials:

How The Body Reacts To Viruses – HMX | Harvard Medical School

This free collection of online learning materials can help with understanding how the body reacts to threats like the coronavirus that causes COVID-19.

Most viruses are not viremic meaning that they do not persist for long periods of time in the blood and are generally not hematogenously spread through the body in people with generally healthy immune systems. A few viruses that are blood borne include human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), Hepatitis B and Hepatitis C. These viruses persist in the blood long-term or for life. “Many other viruses may be found briefly in blood, but they generally don’t persist and are not considered significant “blood-borne” pathogens. Any infectious agent with a blood-borne, or “viraemic” phase has the potential for blood borne transmission, and so may be important for blood transfusions. For many infections, this viraemic period persists until the immune system is able to cure the infection”.

Why are only some viruses transmissible by blood and how are they actually spread?

Why is it only some viruses are transmissible by blood, and how does the virus actually move from person to person?

“Viremia can be maintained only if there is a continuing introduction of virus into the bloodstream from infected tissues to counter the continual removal of virus by macrophages and other cells”. Because of the large amount of leukocytes in the blood circulatory system and the rapid pumping of blood by the heart, most viruses such as influenza and other non-blood-borne viruses are rapidly inactivated and phagocytosized (eaten by phagocytes). Thus, the primary infection path of viruses is directly from cell to nearby cell, via air in the respiratory system, or interstitially in the areas that drain into the lymph system. Once deeper in the lymph system and lymph nodes, viruses again tend to be rapidly inactivated and phagocytosized due to abundance of leukocytes in those areas.

“Fluid from circulating blood leaks into the tissues of the body by capillary action, carrying nutrients to the cells. The fluid bathes the tissues as interstitial fluid, collecting waste products, bacteria, and damaged cells, and then drains as lymph into the lymphatic capillaries and lymphatic vessels. These vessels carry the lymph throughout the body, passing through numerous lymph nodes which filter out unwanted materials such as [viruses], bacteria and damaged cells. Lymph then passes into much larger lymph vessels known as lymph ducts. The right lymphatic duct drains the right side of the region and the much larger left lymphatic duct, known as the thoracic duct, drains the left side of the body. The ducts empty into the subclavian veins to return to the blood circulation.”

By the time the lymph system returns the fluid to the blood circulatory system, a healthy immune system has removed any viruses. This means that people with healthy immune systems have very little viral load within their blood circulatory system even when infected (except for the few blood-borne virus types noted above). In general, the more severe the case, the more likely that some viral load will be detectable in the circulating blood. A study found that in 6 of 6 cases of COVID-19 where blood was found PCR positive, the case was severe; none of the cases where blood was PCR positive were mild. This implies that case severity may be minimized by improving viral elimination within the lymphatic system prior to lymph being returned to the blood circulatory system.

Detectable 2019-nCoV viral RNA in blood is a strong indicator for the further clinical severity

The novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) infection caused pneumonia. we retrospectively analyzed the virus presence in the pharyngeal swab, blood, and the anal swab detected by real-time PCR in the clinical lab. Unexpectedly, the 2109-nCoV RNA was readily detected …

Putting testing to the test: Using our body’s immune response to fight COVID-19 | Swiss Re

As the world emerges from the crisis, testing will continue to be key and will demand significant investment in time and innovation.

Not just antibodies: B cells and T cells mediate immunity to COVID-19

Here, Cox and Brokstad briefly discuss T cell- and B cell-mediated immunity to SARS-CoV-2, stressing that a lack of serum antibodies does not necessarily equate with a lack of immunity to the virus.

https://bio.libretexts.org/Bookshelves/Microbiology/Book%3A_Microbiology_(Boundless)/11%3A_Immunology/11.01%3A_Overview_of_Immunity/11.1C%3A_Overview_of_the_Immune_System

Explained: How a COVID-19 Serology Test Works And Obstacles to its Use

COVID-19 serology tests, also known as antibody tests, are currently receiving heightened attention and scrutiny.

Chronological evolution of IgM, IgA, IgG and neutralisation antibodies after infection with SARS-associated coronavirus – PubMed

Abstract Serum levels of IgG, IgM and IgA against severe acute respiratory distress syndrome (SARS)-associated coronavirus (SARS-CoV) were detected serially with the use of immunofluorescent antibody assays in 30 patients with SARS. Seroconversion for IgG (mean 10 days) occurred simultaneously, or 1…

Estimated Timeline for Detection of SARS-CoV-2 Infection Relative to Symptom Onset #COVID19 #SARSCOV2 …

Estimated Timeline for Detection of SARS-CoV-2 Infection Relative to Symptom Onset #COVID19 #SARSCOV2 #PCR #Serology #Antibodies #Antibody #Laboratory #Testing #Interpretation #Timeline

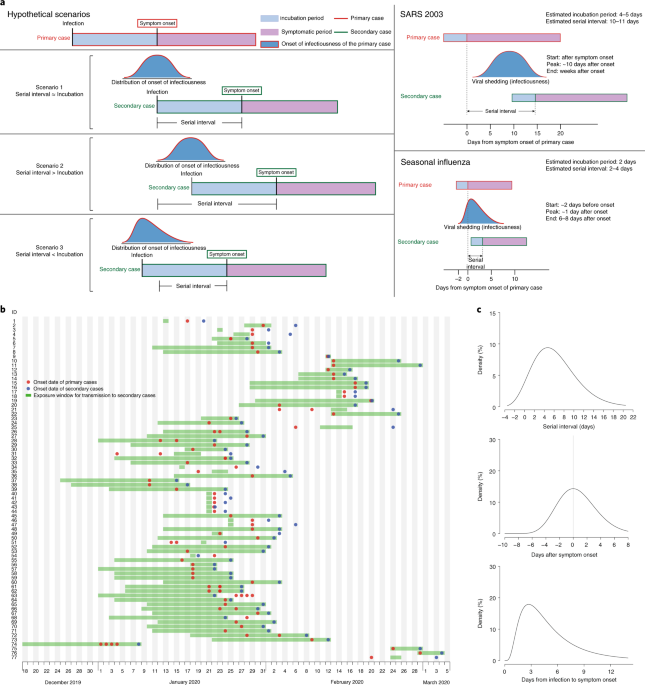

Temporal dynamics in viral shedding and transmissibility of COVID-19

Presymptomatic transmission of SARS-CoV-2 is estimated to account for a substantial proportion of COVID-19 cases.

SARS-CoV-2: The viral shedding vs infectivity dilemma

Since December 2019, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) has infected over four million people worldwide. There are multiple reports of prolonged viral shedding in people infected with SARS-CoV-2 but the presence of viral RNA …

Transmission of SARS-CoV-2: A Review of Viral, Host, and Environmental Factors | Annals of Internal Medicine

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), the etiologic agent of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), has spread globally in a few short months. Substantial evidence now support…

Virus shedding dynamics in asymptomatic and mildly symptomatic patients infected with SARS-CoV-2

Asymptomatic patients, together with those with mild symptoms of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), may play an important role in severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) transmission. However, the dynamics of virus shedding during …

NEJM Journal Watch: Summaries of and commentary on original medical and scientific articles from key medical journals

NEJM Journal Watch reviews over 250 scientific and medical journals to present important clinical research findings and insightful commentary

PLOS Pathogens: Page Not Found

Looking for an article? Use the article search box above, or try the advanced search form.

Quantitative COVID-19 infectiousness estimate correlating with viral shedding and culturability suggests 68% pre-symptomatic transmissions

A person clinically diagnosed with COVID 19 can infect others for several days before and after the onset of symptoms. At the epidemiological level, this information on how infectious someone is lies embedded implicitly in the serial interval data. Other clinical indicators of infectiousness based o…

COVID-19 update: Transmission 5% or less among close contacts

New insights from China, CDC

Rapid coronavirus testing arrives in Blaine County

As cities across the Wood River Valley look ahead to reopening, questions about COVID-19 remain—what percentage of the population is infected, which groups are most at risk and whether it’s

COVID-19 Antibody Testing – Hudson Medical

COVID-19 antibody testing is used to see if your body has developed antibodies can be done with a simple finger stick and a few drops of blood.

After the Coronavirus Peak, What’s Next? | Morgan Stanley

As the growth in new cases of infection appears to be slowing in some hard-hit regions, what comes next? A look at what needs to happen before the world can “reopen.”

Biologic Products DNA to IND Timeline in 9 Months – Yes it can be done! – WuXi Biologics

Article originally published on blog April 11, 2019 Biologic Products DNA to IND Timeline in 9 Months – Yes it can be done! The ability to rapidly develop biologic products from conception to human clinical trials is an increasingly important aspect of controlling drug development costs and in ex…

Coronavirus Testing | COVID-19 Antibodies Test | Access Medical Labs

What is the COVID-19 Test and how can I get one? Discover the answers to this corona virus question and more at Access Medical Labs.

DST funded startup develops kits for testing asymptomatic COVID-19 infections & gears up for vaccine production | Department Of Science & Technology

The Department of Science & Technology plays a pivotal role in promotion of science & technology in the country.

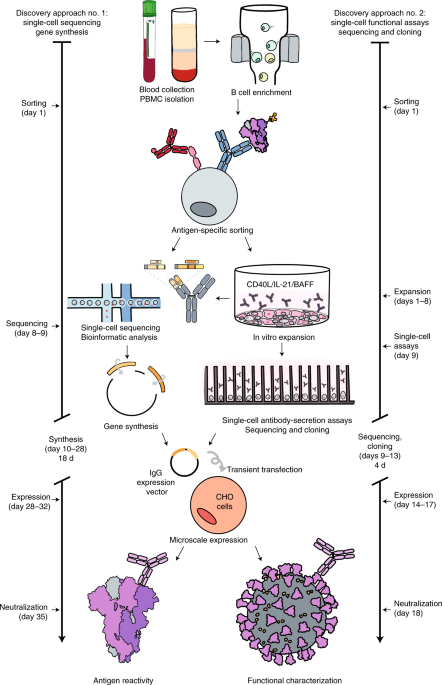

Rapid isolation and profiling of a diverse panel of human monoclonal antibodies targeting the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein

A platform for rapid antibody discovery enabled the isolation of hundreds of human monoclonal antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 and the prioritization of potent antibody candidates for clinical trials in patients with COVID-19.

Antibody Test Results of Two Washington Residents Throw Into Question Timeline of Coronavirus’s U.S. Arrival

She came down with a bug two days after Christmas, and for the next week or so, Jean, a 64-year-old retired nurse, suffered through a series of worsening symptoms: a

Hepatitis A

Hepatitis A is a common viral illness worldwide, although the incidence in the United States has diminished in recent years as a result of extended immunization practices. Hepatitis A virus is transmitted through fecal-oral contamination, and there are occasional outbreaks through food sources. Youn…

The beneficial effects of varicella zoster virus

Varicella zoster virus behaves differently from other herpes viruses as it differs from them in many aspects.

COVID-19-Testing-Landscape-Final.pdf

http://hopkinsglobalhealth.org/assets/documents/COVID_Diagnostics_GH_30April2020_(3).pdf

Loading...

Loading...

Loading…

Loading…

Loading…

Loading…